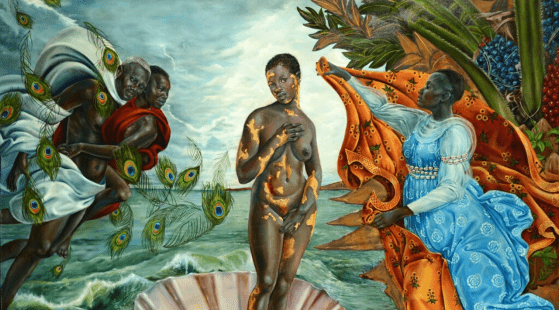

In 2017, Afro-Cuban artist Harmonia Rosales unveiled a series of paintings that aimed to question the common—and eurocentric—understanding of art. In her exhibit Black Imagery to Counter Hegemony, Rosales reimagined iconic paintings with Black women at the center. In one striking visual, Rosales recreates “The Birth of Venus” in her painting “The Birth of Oshun” where a Black woman with markings of gold vitiligo stands as the focal point. Instead of man-creating-man like Michaelangelo’s “Creation of Adam,” Rosales depicts two Black women, hands outstretched in the famous scene. Rosales says her paintings are “replacing the white male figures (the most represented) with people [she believes] have been the least represented. By contemporizing the meaning behind these iconic paintings we can begin to recondition our minds to accept new concepts of human value.” Her work asks the question— who exactly gets to be represented, valued, and celebrated in art?

The art world has long been dominated by white men, with women and artists of color not only receiving less acclaim but also making up significantly less of the artwork in museums. There is no shortage of talented Black women artists but, regardless, the art world is missing their perspective.

In a piece appearing in the New York Times, nine Black artists discuss their work, with many contemplating the role of the white gaze. New York-based artist Renee Cox creates works of empowered Black women, where the subjects are the ones to gaze upon the observer. Cox says, “I return the power of the gaze to the subject — and usually my subjects are black… They don’t fall into the stereotypes of black people that white people have created.” Visual artist Calida Rawles shares how her work relates to the Black female identity. She says, “I wanted to discuss the intersectionality of the black female experience, as well as the theory of triple consciousness, which stipulates that black women in this country view themselves through three lenses: the American experience, largely defined by white men; the female experience, generally written by white women; and the black experience, usually associated with black men. To make work, for me, is to seek a kind of spiritual healing from all of that.”

The experiences of Black women are missing from the media, and the arts are no exception. Institutional discrimination and implicit bias are certainly at play. In an interview with The Guardian, British artist Michaela Yearwood-Dan recounts the microaggressions she faced— and currently faces—as a Black woman in the arts. Yearwood-Dan comments on the lack of inclusion, saying, “I’m forever the only black person in a room. I’ve been racially discriminated against at shows that I’ve been in.” Performance artist Ayana Evans explained to BOMB magazine that she’s taken to using buzzwords like “feminism,” “radical feminism,” and “body politics” to describe her work about Black womanhood to ensure she receives press. “That is not a popular thing, saying your work is about black women. Somebody told me that a long time ago.”

Take Action! Buy, celebrate, and support art by Black women. Need a place to start? Check out this list of organizations that “foster the careers of aspiring black creatives in a variety of ways.”